Written and Photographed by ADRIAN WARREN

Pubished in BBC WILDLIFE Magazine; February 1997 Page 22- 25

Life in the ring-tailed lemur community is a fascinating social whirl.

And the arrival of a little gem of a lemur-Sapphire-provided a natural focus for their human observers. Adrian Warren tells the tale of the ringtails

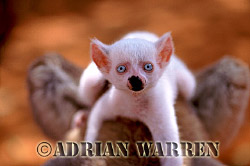

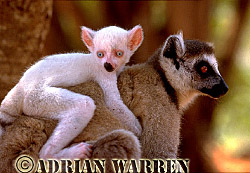

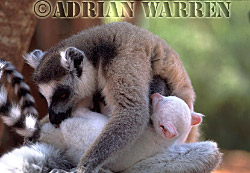

Sapphire was just a few days old when we first saw him. Like any new-born lemur, he looked small and fragile and clung tightly to his mother. And yet one look was enough to convince us that he was something special. His fur was white instead of grey, and his eyes were a sparkling blue. If any animal had to be called Sapphire it was him.

Albino ring-tailed lemurs do turn up from time to time, but Sapphire wasn't a true albino, for he had black rings on his tail, as well as those striking blue eyes. He was a real rarity, and he was to play a starring role in the film we were making about a year in the life of ring-tailed lemurs in the forest of Berenty, southern Madagascar.

It was September -the time of the year when ring-tails have their young. The dry season was lingering, and it was oppressively hot. We sat in the shade of a giant tamarind tree and watched as Sapphire's companions took their customary siesta. Sunlight filtered through the feathery green leaves, dappling the soft grey fur of the ring-tails as they slumped, like lifeless puppets, over the branches.

Our guide to this peaceful scene was lemur-expert Professor Alison Jolly of Princeton University, who has been studying ring-tails at Berenty since the" 1960s. Alison's research has shown that ring-tail society is headed by females, among whom there is a fiercely defended, shifting hierarchy. For most of the year (and even in the mating season), the males, who have their own separate hierarchy, are kept under female control. Each individual in a troop knows his or her place on the social ladder and each has a close group of associates, friends and relatives with whom he or she spends most of the time, whether awake or asleep.

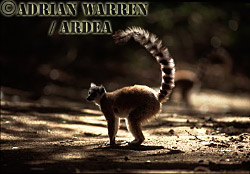

Ring-tails are the most social of the lemurs. They band together in large troops, whereas many other lemurs live in small groups that are really little more than extended families. The troop we were watching was made up of 27 individuals, a large number even by ring-tail standards. Living in large troops brings major benefits: there are more pairs of eyes and ears to sense danger and more partners to choose from when the time comes for mating.

To thrive in this complex society, ring-tails must be able to recognise one another as individuals. They have developed elaborate methods of communication as a result. Their calls are many and varied, and their conversation is almost continuous as they go about their daily routine. They also rely heavily on body language and a few facial gestures.

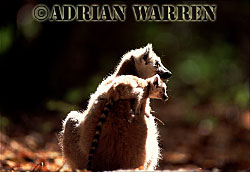

We looked forward to following young Sapphire's progress over the coming months as he learned these crucial skills. But for now, there were other things to think about, in the shape of two late arrivals to the troop -a pair of twins, one of each sex. Compared to Sapphire, they were unbelievably tiny, as twins tend to be. Partly because of their size, and partly because they were born late, to a subordinate mother, we knew they had little hope of both surviving.

Considering her position in the female hierarchy, the twins' mother was surprisingly calm and conscientious, often seeking out a quiet spot some distance away from her companions where she could give her youngsters her full attention. We knew she would have a tough time providing enough milk for two hungry mouths in the coming weeks. Everything was parched dry, the trees were shedding their leaves, and though there was plenty of food to be had in the shape of tamarind fruit, there was little or no moisture. It was as if the whole forest was holding its breath, waiting for the first drops of much-needed rain.

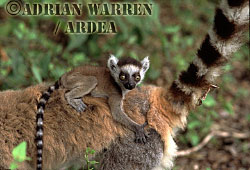

Life isn't easy for little ring-tails at the best of times. About half of all infants die in their first year, many from injuries, some as a result of falls from high branches. At birth, they are almost completely helpless, though they can use their tiny hands and feet to grasp their mothers' fur in a vice-like grip while being carried at speed through the treetops. At first, they are carried beneath the belly -within easy reach of a nipple. As they grow, they switch to travelling on their mothers' backs. From this vantage point they can observe how their mothers are treated by other troop members.

A high-ranking mother, for instance, enjoys special treatment: her infant will see that she is confident and that she elicits submissive reactions from other members of the troop. Females change rank every two or three years, however, and the high-status infant may have to fight for her future rank -but she'll know how to go about it.

By contrast, a low-ranking mother is constantly bullied by higher-ranking females and must work hard to protect her infant. Her youngster learns how to be submissive. Perhaps it will grow up to be a low-ranking male or a nervous, inadequate mother- assuming it lives that long.

As the weeks passed, Sapphire grew steadily. He became a confident youngster, forming play groups with other infants of his own age. He was adventurous and inquisitive, wandering away from his mother to clamber along branches and make contact with other troop members -typical behaviour for a young male ring-tail.

Females, in this female-dominated world, are as rambunctious as the males, but they also remain close to their mothers, learning skills that will stand them in good stead when they have babies of their own. Sometimes they get the chance to act as 'aunts', holding and grooming their baby brothers or sisters.

The relationships that females forge with their mothers are long-lasting -for females never leave their natal troop. Males, on the other hand, grow up to become wanderers, staying with their natal troop only for a short while. After leaving home, they spend their time roaming the forest with other males, looking for other troops to join.

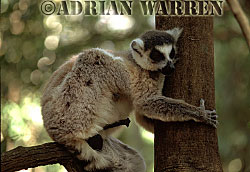

As far as Sapphire was concerned, that .was all in the future. For the moment his life slipped into a reassuring daily routine. This would begin at dawn, as the troop took a short journey on the forest floor, from a favourite sleeping tree to a huge and ancient tamarind.

Ring-tails are completely at home in the treetops, the bare upper branches of the tamarind made an ideal arena for a morning assembly. Here the lemurs would climb to their favourite perches to bask in the first warming rays of sunshine. It was a time to be with friends, to groom, to play or to tend to the needs of infants. One of the males would climb to a perch on one of the highest branches to sing, sending a message far across the forest proclaiming the troop'sownership of this treasured tree.

Then the troop, led by the senior females, would head down to the cooler glades of the forest to feed. As they moved and fed, they would reinforce their territorial claim by scent-marking. Females would back up on a sapling to leave a genital smear, whereas the males would also use their special wrist glands, armed with a horny pad, to score the surface of the sapling's bark and so leave a more permanent signature.

Eventually, the troop would arrive at one of several siesta trees dotted across their territory. Here they would sleep for two hours, or longer if the day was particularly hot. The afternoon would be a re-run of the morning, with the troop moving in a wide circle -over most of their range -before returning to a sleeping tree not far from the ancient tamarind where the day began. With an abundance of leaves, fruit and flowers on which to feed, a troop's territory can be quite small.

The troop followed its regular routine until November, when the rains began -an event that brought relief to forest animals and farmers, alike. The first storm was an impressive one. The clouds had built up for days, and finally, to the accompaniment of lightning and rolls of thunder, the first drops of rain fell, developing into a downpour that flooded huge areas of the forest.

|

Scent marking: female |

|

Scent marking: male |

Most of the ring-tail infants were big enough to cope with the numbing cold of the rainy season, but we were anxious about the twins, because they'd been born late and were still tiny. Miraculously, they made it, as did Sapphire. As the weeks passed, all three continued to grow into strong little lemurs. The rains brought fresh, luxuriant growth and a plentiful supply of food for the troop. The youngsters, no longer solely dependent on milk, watched carefully as their mothers chose certain plants and ignored others, then did the same.

April came, and the rainy season began to ebb. For the ring-tails it was time to prepare for mating -a brief, frenzied annual event that throws the relative calm of the troop into chaos. We watched as the troop members followed a familiar route through their territory towards a feeding tree. They walked more or less in a line, sauntering, unhurried -the dominant females and youngsters in front, the subordinate male bringing up the rear. Suddenly, one of the young females marked a thin sapling. A confident young male, not far behind, went to the sapling to sniff her scent, then enthusiastically added own, using his wrist glands. Sexual chemistry was definitely in the air.

During the days that followed, the male stay close to this particular female. She didn't discourage him. Together, they would wander so distance away from the rest of the troop to a quiet spot where they would cuddle and groom one another, forming a 'consort bond'. Corn bonds are sometimes short-lived, but they can be highly significant. With luck, the bond will last long enough for the partners to mate- though there's always a risk that it will disappear in the chaos of the mating frenzy (Frenzy is an apt word. With hormones in full flow, dominance ranks are forgotten as males challenge each other night and day. As an aggressor approaches his opponent, he rubs the soft fur of his tail with his wrist glands, anointing it with his scent. Then, continuing his approach, he waves his tail in the air over his back to waft his scent in the direction of the other male).

These 'stink fights' are often bloodless, but sometimes the contenders resort to using their razor-sharp teeth and claws. They slash each other on head, flank or thigh like knife-fighters. And yet the most dominant males are not necessarily the most successful at mating: low-ranking males sometimes fight the leaders to a standstill, and win the chance to mount females. Chaos reigns in this free-for-all, which results in some defeated males leaving the troop to try their luck elsewhere the following year. Calm only returns to the troop once the females are no longer in oestrus.

Some consort bonds remain intact outside the breeding season. A female may frequently be seen in the company of a certain male, who shows great affection towards her and tries to groom and cuddle her infant. He may or may not be her infant's father.

When it comes to choosing a partner for one of these longer-term relationships, a female ring- tail may prefer a mellow, non-aggressive male. The upshot is that some of these self-assured, older males spend virtually all the year in the close company of females, being pampered and groomed.

Ring-tail society is highly sophisticated, and it's difficult at times not to notice echoes of their behaviour patterns in our own. In fact, the hardest part of filming was recording mothers' reactions to the death of their infants. We were braced for it, but as we followed 'our' youngsters, we kept hoping that this year they would somehow all survive. It could not happen, of course. Death came to some, including Sapphire, as it does each year. But in the end, those who lived became strong and independent, cavorting around their mothers as the annual cycle began again. As we left, there were now 30 lemurs in the troop awaiting next year's new babies: the younger brothers and sisters of Sapphire, the twins and their playmates.

Found nowhere else in the world; lemurs are an evolutionary one-off Lemurs are primates, members of the group that includes monkeys, apes and ourselves. Compared to other primates, they are less clever with their hands, rely more on the sense of smell and have relatively small brains. Today, there are 32 species in 14 genera, all surviving in Madagascar, Where they evolved in isolation.

Fifty million years ago, the lemurs' 'prosimian' ancestors -probably much like todays's tiny mouse lemurs -were very successful animals in the vast tropical and subtropical forests all the way from America to eastern Asia. Their small size meant that they had to avoid the harsh temperature ranges of the daytime and also made them slaves to an easily digested, high-energy diet of insects and fruit.

Gradually larger lemurs evolved -and new doors began to open. Large size enabled these new forms to lose or absorb heat more slowly than their tiny forbears and meant they could operate with a slower metabolism. That allowed them to switch to a diet of leaves, which are more difficult to digest and yield less energy than fruit or insects. Because leaves are abundant, there was less competition for food, and so they were able to become more social -which is exactly what the ancestors of today's ring-tails did. That trend demanded greater intelligence to cope with more complex communication and recognition of other members of the troop.

Madagascar provided the early lemurs with a tremendous evolutionary opportunity. Though the fossil record is thin, it seems possible that the many kinds of lemurs that have existed on the island arose from a single ancestor species, which may have arrived by accident from the mainland of Africa, perhaps on a floating mat of vegetation broken off in a flash flood and swept out to sea, before being deposited on a lonely beach somewhere on Madagascar's west coast.

Whatever the exact details, the lemurs encountered little competition in their new home and went on to become extraordinarily diverse, producing more than 40 species. They held their own until the arrival of humans in the last 2,000 years. Since then, there have been many extinctions. Just a few tiny corners of pristine Madagascar survive, and the forest of Berenty, with its ring-tailed lemurs, is one of them.

When Alison Jolly, the world authority on lemurs, first decided to study ring-tails, she scoured Madagascar for a suitable study site. She found what she was looking for in the forest at Berenty, in the south of the island, where the lemur troops were large and could be followed through the dappled glades and giant tamarind trees for hours at a time.

Subsequently, many other scientists followed her to this wonderful oasis of forest surrounded by farmland. The Berenty forest is protected by its owners, the de Heaulme family.