|

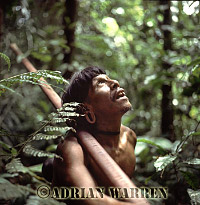

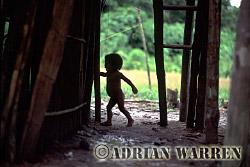

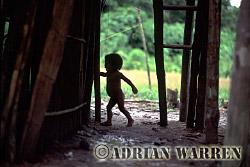

Caempaede hunting with Blowgun, 1983 |

|

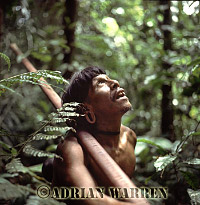

Caempaede and Jim Yost, 1983 |

Jim knows that tourists often brag that they had "no impact" upon the Waorani, because they left nothing behind, but such simplistic notions are foolish. Those who deny the typical tourist pocket knife, backpack, camera or clothing establish a sense of self-deprivation among the Waorani, one that motivates them to seek those goods at all costs, even at the cost of a traditional way of life. All contact carries consequences, some bad, some good; only those who are sensitive enough to be aware of that fact can take steps to try to ensure that their impact is more positive than negative.

By 1985, the traditional way of life had almost disappeared, with the exception of Tagae's group, who were still living in secret isolation, somewhere along the Curaray river. Their days were numbered though as the outside world encroached on traditional Waorani lands from all sides. Oil companies, colonists, missionaries, and travelers threatened the privacy that Taga's group sought to maintain. In 1987, two Ecuadorian missionaries with several years' experience working among Waorani communities, Capuchin priest Padre Alexandro La Baca and Nun Ines Arango, hoped to contact Tagae's group before the devastation brought by oil exploration drove them to extinction, or into violent confrontations with oil men. In full knowledge of Tagae's fearsome reputation, and the fact that no one who had approached them had ever come out alive, the two missionaries were dropped by an oil company helicopter close to Tagae's settlement. Two days later, the air crew returned to find the dead bodies of both. They had been speared to death. It was predictable, perhaps, but at the same time tragic. Reprisals by the oil companies or the military were feared, and indeed may have happened. For Tagae's group, the writing was on the wall.

|

Waorani Indian girls, using Achiote for face decoration, rio Cononaco, 2002 |

Pressure from outsiders continued to increase, driven by a relentless thirst for oil. Dramatic changes were enveloping the Waorani; the oil companies seemed unstoppable, timber harvesters were felling trees within the boundaries of their hunting grounds, diseases the Waorani never knew were challenging their health, and Spanish schools were keeping children out of the forest and teaching that the traditional Waorani ways were of no value.

Numerous outsiders, particularly Quichua and Shuar, were assuming the role of spokespersons on behalf of the Waorani around 1981, usually without the Waorani even being aware they were doing so. These "spokespersons" were representing the Waorani to the Ecuadorian government, to oil companies, to international aid organizations and to the media. At times they obligated the Waorani to things they had no knowledge of and at other times they made "requests" on behalf of the Waorani and then made off with the funds or whatever they could glean by doing so - again without Wao knowledge of it. The younger Waorani who were learning Spanish and outside ways began to realize what was happening and decided it was time to organize themselves so they could be their own representatives to the outside world. The last project Jim Yost undertook before he left Wao land in 1982 was to spend 6 months travelling from village to village talking to the Waorani about leadership issues - explaining to them about representative government, legal organization, government functions, "Federations", "Comunas", etc. Jim had leaders from other tribes like the Cofanes come and talk about their tribal organizations as well. Jim impressed upon them the need to organize if they were going to meet the exploiters head-on. The older generation saw no need to depart from their egalitarian-independent-isolationist ways, but the younger ones could see there were problems building on the horizon and became interested in organising. It was a difficult decision for Jim: on the one hand he appreciated the old way of doing things and did not want to direct change; but on the other he saw that they needed some way for each community to have its voice heard and that they needed to unite if they were to gain any control over the external forces impinging upon them. Jim urged them to form something legal that would include all communities. Eventually, the increased oil company presence brought the issue to a head. At that point Jim recommended to the oil companies that they begin interacting with an official Wao-sanctioned organization, not with isolated individuals who claimed to be Wao representatives.

ion, representatives of nearly all Waorani communities travelled to Tonaempaedi. There they held a series of meetings intending to establish their own independent organisation, ONHAE, in order to interface directly with the now numerous interests of outsiders impinging on their lives and their territory. With increasing dependence on outsiders, money was beginning to assume an importance the Waorani never previously understood. At the meetings, feelings were strongly divided; some speakers saw advantages with the oil companies as a source of income, others complained that the few dollars they received was very small in comparison to the value of the damage inflicted, and the resources being removed from their land.

|

Tedecawae, 1993 |

From the beginning, a headlong scramble to access manufactured goods like clothing, axes and machetes had drawn Waorani into oil company contact. Even back in 1974, in the hopes of luring helicopters and their booty, Caempaede's group, at Gabado, built helipads with mock scribbling on sticks in imitation of helipad markers. A man called Tedecawae even composed a new song about helicopters in the hopes that singing it would induce helicopters to come bearing gifts. For nearly two decades the Waorani welcomed oil exploration because the seismic lines cleared by company crews made excellent trails for travel or hunting. In addition, the massive wealth of goods, food and new experiences attracted Waorani to seek employment with oil companies as labourers.

|

Caempaede's settlement at Cononaco airstrip |

The encroachment was increasing the pressure on the now confused Waorani to integrate. Caempaede's group moved back to the Cononaco airstrip where, in spite of the risk of diseases brought in by outsiders, they believed they would have more access to material goods; air transport for medical care; and access to schools. Little by little, as all these things began to assume an importance unknown before, they were losing their independence.

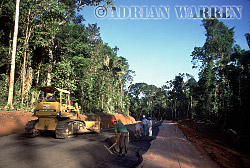

The oil companies continued their encroachment on traditional lands, and the first road was constructed with astonishing speed in 1982. The road, in itself, was relatively benign. But, like the wake from a tanker, it brought with it wave after wave of colonists seeking wealth or escape from trouble elsewhere. Quichuas from the Andes, Quichuas from the rain forest, blacks and mestizos from the Ecuadorian coast, Shuar from the Ecuadorian-Peruvian border, Colombians of various stripes - they all invaded with the persistence of a horde of army ants, consuming the forest in their path. In the vanguard, clearing the way for all of these were an aggressive pack who have low regard for life in general, but for Indians and Waorani in particular. The Waorani were pushed farther and farther into the recesses of the forest.

|

|

A new Oil Company Road in WAORANI INDIANS Territory, Ecuador, 1993 |

Maxus Oil company helicopter, Waorani territory, Ecuador, 1993 |

|

|

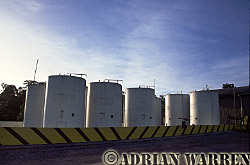

Oil installation, Waorani territory, Ecuador, 1993 |

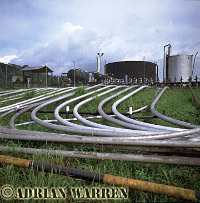

Texaco oil installation, rio Cononaco, Ecuador, 2002 |

The disturbance of a massive influx of outside civilisation in some areas frightened away game animals the Waorani needed to hunt for food, and brought yet more diseases. The history of contact between outside civilisation and indigenous peoples is replete with epidemics taking a heavy toll. The Waorani were fortunate in that the missionaries provided medical treatment and stayed long enough to ensure that epidemics did not decimate them. At one time they were the only line of modern health-care for the Waorani, and today they are still the principal source, particularly for accidents and snakebite. The diseases the Waorani face today give ample testimony that as a people they are inextricably entwined into the international community. The latest strains of colds or influenza quickly find their way into Waorani villages. Most recently, Hepatitis D, Cerebral Malaria, and Chicken Pox, all unknown only a decade ago, have swept through Waorani communities as a result of tourist visits and Waorani travels or work among the cowode.

Outside civilisation also brought pollution. There was no protection for the Waorani against sewage from upstream colonists or oil spillage that caused serious and toxic contamination of water supplies. As if that was not enough, an extensive mining programme was proposed to extract gold, uranium, vanadium, lead, zinc, copper, gypsum, clay, sulphur, bentonite and phosphate. Although the Ecuadorian government ceded legal right to the Waorani for some of their ancestral lands, a total disregard of law and an all-pervading corruption erode the borders of even that concession.

Dayuma, and a Waorani called Moi, made separate trips to Washington as representatives of the Waorani people, paid for by a team of lawyers from the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund, to file petitions on Human Rights. It was a response to the untreated toxic waste products being dumped daily into the natural water drainage in Waorani territory. Their journeys had begun deep in the Ecuadorian Amazon and ended in Washington DC.. Travelling on foot, canoe, bus, train and aeroplane, they had crossed centuries. Tucked into Moi's hand woven palm string bag he had brought from home were his passport, toothbrush, bird feather head dress, and a letter addressed to the President of the United States of America. The letter invited the President to visit the Waorani, to explain to them why the outside world was trying to destroy them. His, and Dayuma's efforts, were in vain. They had hoped, as representatives of their people, to be received by the President, but the closest they came to meeting Bill Clinton was a cardboard effigy that a Polaroid photographer had placed for tourists outside the gates of the White House.

|

Caempaede's settlement at Cononaco airstrip |

By 1995, encroachment on to Waorani lands was out of control. The networks of roads had grown, opening up some seven million hectares of Waorani territory to speculators and colonists. As well as roads, thousands of hectares of forest had been cut and numerous helicopter landing sites prepared. At hundred metre intervals, explosives had been detonated to generate sound waves for seismic analysis, before drilling started. Once the wells were established, contamination from waste products was constant, and discharged onto surrounding land or open pits, from where it found its way into streams. Many streams could no longer support life, but indigenous people had no choice but to use this water for drinking and cooking.

The Waorani, like many indigenous peoples, proved to be easy to exploit. With fundamentally very different attitudes to us they have no concept of land ownership, although they have always had a strong sense of private ownership of goods. Their economic system is one of generalised reciprocity - they have never had the need for a monetary system, since the forest has always provided their basic needs and they do not exploit it for money; and, as an egalitarian society, there are no political leaders; family groups function independently. Outsiders use obvious methods to make indigenous peoples more amenable to land exploitation: gifts are offered, but they are conditional; creating dependency and community destabilisation. They are told that they are backward, that they must change, and embrace the more dominant culture. The results of this are displacement, poverty, declining health, deterioration of community life and devaluation of traditional culture. As the younger Waorani struggle to come to terms with a new and difficult way of life, Caempaede and the other elders are the only direct link with the old ways.